Questions About the Biblical Canon

by Gavin Rumney

Just how we ended up with the Old and New Testaments as we have them today is an interesting tale, one that most of us know little or nothing about.

Most people are aware that Catholic editions of the Bible include sections (in fact whole books such as 1 & 2 Maccabees) not found in standard Protestant versions. Fewer are aware that the Orthodox churches include even more material in their scriptures (such as 3 Maccabees and the Prayer of Manasseh). So, what about that extra material? Or more to the point, why does the 66-book edition most of us are familiar with not include it, and who decides what is and isn't scripture?

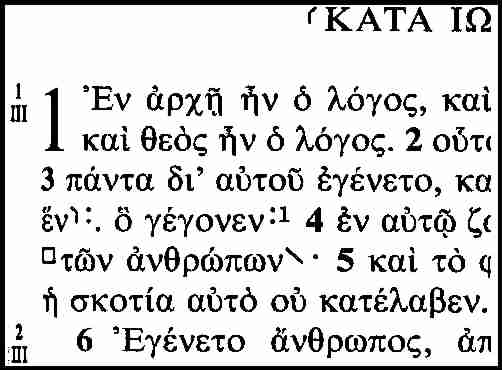

Traditionally, evangelical Christians have circled their wagons around the distinction between genuine writings and "apocrypha". Genuine writings being, of course, their 66-book Bible; apocrypha (sometimes called pseudepigrapha) conveniently being everything else. Evangelicals have been quick to assert, for example, an "obvious qualitative difference" between the two. Unfortunately there is an obvious qualitative difference between books within the Bible as well, as anyone will know who has compared the Gospel of John with the Book of Numbers.

The Creation of the Canon

But wasn't the whole thing decided at the very start of the Christian Church? Here's where things get interesting. The Jewish canon (Old Testament) first reached its present form after 70 AD with a gathering of rabbis at a place called Jamnia (Jabneh), 24 km south of modern Tel Aviv. Notice the date, this is decades after the establishment of the church. Paul has left the scene and the events related in Acts are already history. Notice too that this was a Jewish council. There was no Christian input into the process at all. In fact the Jamnia council was called, in part, in order to distinguish the Jewish religion from its troublesome Christian offspring.

It is not surprising then that the Christians rejected this Jewish Old Testament canon, and continued to use the Septuagint, a Greek version of the Old Testament produced in Alexandria beginning in the third century BC. The Septuagint included several books and additional passages which the rabbis now rejected, and are no longer found in the standard editions today. In part their decision was based on the fact that there were no Hebrew originals for this additional material (ironically, the discovery of the Dead Sea Scrolls demonstrated that the rabbis were, in part, mistaken).

Christianity, however, was to continue to use the Septuagint based "Alexandrian Canon" for another thousand years! This makes it quite hard to see how modern fundamentalists can justify their present canon as being either "apostolic" or "determined by the Holy Spirit".

What about the New Testament? The New Testament canon was a matter of debate for centuries. It first reached its present form as late as 367 AD when Athanasius, the bishop of Alexandria, compiled a list of recognized books which agrees with the ones we now have. Three hundred years is a long time by anyone's reckoning. If the writing of the New Testament documents had started back in 1840, we wouldn't get to see the final product until the year 2140! Although it seems hard to imagine, during this 300 year period Christians of all persuasions pursued their faith without the benefit of the Bible as we know it today.

As for the gospels, it took till 185 AD for a consensus to emerge about which were the authoritative ones, and only then thanks to a pronouncement on the subject by Irenaeus. For another 200 years these four gospels were to put together with a variety of different additional documents according to the best judgments of different Christian communities.

As late as 200 AD the Church at Rome still didn't consider the books of Hebrews, James, 1 Peter or 2 Peter as scripture. However they did include two "apocryphal" works: The Apocalypse of Peter and The Wisdom of Solomon.

In the end the final selection was to be a narrow thing, with the popular Shepherd of Hermas missing a listing in Athanasius' canon by a whisker, while the controversial books of Revelation and Hebrews squeaked through. The main criteria used in the selection was that the documents should come from the pens of those with first hand knowledge of the events surrounding the creation of the church. We now know that Athanasius made several wrong calls. For example, several of the letters attributed to Paul (such as the epistles to Timothy) are in fact later documents.

And one has to wonder also, how Christians who vehemently reject Catholic tradition and authority in all other matters, can be so dogmatic in their agreement with this particular tradition. The events surrounding the creation of our New Testament can give little support to those adhering to a strict biblicist view.

The Reformation

The reformation brought about another shake up when Martin Luther banished the Septuagint based Old Testament canon and replaced it with the shorter Jewish canon. The additional books, said Luther, were good to read but not to be considered as scripture. This broke a tradition going back over a thousand years, one which is still retained in Catholicism and Orthodoxy.

It is this edited canon of the Old Testament that is now in almost universal use, and is regarded as authoritative amongst traditions as diverse as Presbyterianism and Jehovah's Witnesses. Those churches that seek to identify themselves with the "Apostolic era" to validate their beliefs (rather than later traditions which they believe are flawed), seem to be blind to the fact that their Old Testament canon is far from "apostolic".

Few Christians realize that Luther's bold redrawing of the boundaries of scripture almost flowed through into the New Testament as well. The reformer had labeled the Letter of James "an epistle of straw", and some Lutheran editions of the Bible followed through by relegating it, along with Hebrews, Jude and Revelation, to a special appendix at the back of the New Testament. In effect this placed them in a de facto New Testament apocrypha. This from the man who coined the very phrase sola scriptura!

However, the practice failed to catch on (although it persisted through a number of German editions of the Bible over many years). The precedent is still a fascinating one. It demonstrates that the original Protestant tradition could, during its formative years, happily make major adjustments to the canon of scripture. The criteria was not some Joseph Smith-style revelation, but reason and judgment based on the best scholarship available at the time.

Canon? Which Canon?

Much more could be added. For example:

To complicate matters even further, modern scholars have identified two new gospels that cast authentic light on the church's earliest beginnings. One is the reconstructed "Q" Gospel that underlies Matthew and Luke. The majority of New Testament scholars believe that this Sayings Gospel was reworked by the later writers to fit in with the brief narrative framework created by Mark, as they sought to flesh out the scanty factual material available to them about Jesus. It comes as a huge shock to most Christians to learn that the authorship of these later documents (Matthew and Luke) is pseudonymous.

- The Ethiopian Orthodox church adds four extra books to its New Testament, and another two to the Old Testament.

- Writing around 300 AD Eusebius, the historian of the early church, listed Hebrews, James, 2 Peter, 2 & 3 John, Jude and Revelation as either dubious or false.

- The Syrian Orthodox tradition continues to reject 2 Peter, 2 & 3 John, Jude and Revelation.

- Irenaeus, who is credited with standardizing the number of gospels at the present four, included a book called The Revelation of Peter in his canon.

- Codex Sinaiticus, the oldest complete New Testament manuscript that has come down to us (fourth century AD) includes Barnabas and The Shepherd of Hermas.

- As late as the fifth century the Codex Alexandrinus included 1 & 2 Clement.

The second document is the Gospel of Thomas, one of the Nag Hammadi texts discovered in Egypt in 1945. This gospel includes some passages with close parallels to canonical material, but also some entirely new sayings of Jesus that circulated in the early church. Much of this material is believed to be at least as old as the gospels of Mark and "Q".

The canon of the Bible did not drop out of the heavens one day, fully formed and divided tidily into proof texts. A basic knowledge of the process of canonization ensures that any concept of inerrancy is untenable, a weakness of those who have (to quote Luther) "swallowed the Holy Spirit feathers and all".

Even today, there is no single Christian canon of scripture, and in fact there never has been.

Further reading

- Borg, Marcus. The Lost Gospel: Q. Seastone, 1996, 1999.

- Funk, Robert and Hoover, Roy. The Five Gospels. Scribner, 1993, 1996.

- Helms, Randel. Who Wrote the Gospels? Millennium, 1997.

- Mack, Burton. Who Wrote the New Testament? Harper Collins, 1995.

- Mack, Burton. The Lost Gospel: The Book of Q and Christian Origins. Harper Collins, 1993.

- Miller, Robert (ed) The Complete Gospels. Harper Collins, 1992, 1994.

Copyright © 1999, 2001 Gavin Rumney

Last updated July 2001e-mail: missingdimension@ihug.co.nz

Home page: The Missing Dimension