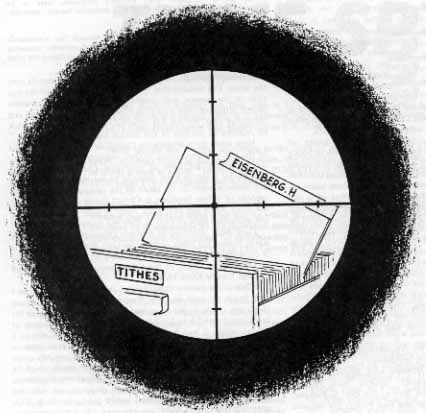

EXECUTIVE ACTION

"Hello. Ted? This is Bob... Remember that tithing re search? I think we're going to have problems with Harry."

Editor: At beautiful, serene Ambassador College a person who is too concerned about truth may suddenly find himself living in a hostile environment. His personal quest for truth may not be regarded as dangerous or heretical as long as his voice is not heard by too many people; but if he is eloquent, or in a position to influence minds in the Ambassador entity, then his quest for truth will be regarded as a great threat.

After Ambassador College ascended to a position of limited prestige among fundamentalist institutions, and while in the midst of accumulating perhaps the most effective propaganda machinery of all such institutions, there occurred the simultaneous accident of accepting a student who regarded the acknowledgment of truth as paramount.

By the time this happened, Garner Ted Armstrong had become a major industry. The Worldwide Church of God had become Ted's religious arm of global influence and the church's Doctrinal Committee had become an efficient oppressor of truth.

The following account, written by Harry Eisenberg, is an account of character assassination. It clearly explains how truth is suppressed inside the Ambassador entity and how the one who discovers it must become silent, giving way to the personal doctrines of those in power, or be removed.

Before his discovery, Harry Eisenberg was an employee of Ambassador College. He is the author of eight major articles published for Ambassador under his by-line, as well as the author of numerous articles written for others or published under no by-line. Here is his story:

Quite by coincidence I am writing this article on the main campus of the University of Maryland. As is the case with virtually every other institution of higher learning, considerable research into both the sciences and humanities has been undertaken here. The purpose of the university is not only to educate students, but to provide new knowledge and answers to questions affecting our society.

Colleges and universities have in fact been the major vehicle for providing society with new knowledge in just about every field. The student, especially the graduate student, is on campus not only to absorb knowledge, but also to make a contribution to the body of knowledge extant in his particular field. To use a familiar phrase, he is expected to give as well as to get!

One would think this principle should hold true for Ambassador College as well. Unfortunately, this has not been the case. This is due to a basic difference between Ambassador College and other institutions of higher learning.

Whereas most universities exist to promote the advancement of knowledge and to pass it on to their students, Ambassador College exists to promulgate to the public the knowledge and values of its founder, Herbert W. Armstrong. New discoveries and/or contributions to knowledge are often not welcome there. For one thing, such new discoveries are not, generally speaking, in keeping with the primary aim, which is the dissemination of existing knowledge. Furthermore, should any new concept uncovered through the research of a faculty member or student conflict even remotely with the views of the founder, such research is utterly unwelcome, as Herbert Armstrong's views are regarded as sacrosanct and inspired.

For example, one student wrote a research paper for an Ambassador theology class, claiming that the scriptures speak of a spirit in animals as well as a spirit in man. He provided considerable evidence to support his contention. Upon presenting the paper to his instructors, the student was urged to keep his ideas to himself. It seems the spirit in man and the idea that animals differ from man is a pet concept of Mr. Armstrong's, and the theology instructors were afraid to present the Student's findings to him.

The following semester the student was not allowed to register for classes and was expelled from the college. He was charged with the crime of "highbrowing the ministers", whatever that means. The loss was Ambassador's, not the student's.

I was a paid researcher on the staff of Ambassador College for over four years. Generally speaking, my work involved providing "proofs" for the pet concepts and theories held by Mr. Herbert Armstrong and/or his son, Garner Ted. Occasionally, I was successful as in the case of an article entitled "Did Jesus Have Long Hair?" This article attempted to show that there is historical evidence proving that Jesus did not necessarily wear long hair, as he is often pictured today.

My article was widely reprinted and resulted in a personal full-page interview in a major Los Angeles daily. It was one of few articles which have cast Ambassador College in a good light. It was met with complete silence by an administration which feels any publicity should he its own private realm.

In January 1973, I was asked by my supervisor, Brian Knowles, to research the subject of tithing. In particular, Mr. Knowles was interested in learning who paid what to whom and how in ancient Israel.

And so I began a systematic study of the tithing doctrine by listing each Biblical verse which in any way refers to tithing. What followed was a study of commentaries, encyclopedias arid various historical sources. The result was inevitable! I came to see that the tithing concept as promulgated by Ambassador College and the Worldwide Church of God was contrary to both the Old and the New Testaments.

Scripture makes it plain that the right to collect tithes was given to the Levitical priesthood in exchange for their service in the Temple. There is no evidence that this right was ever passed on to the New Testament Church. The Encyclopedias BRITANNICA and AMERICANA both confirm this view when they state the early New Testament Church did not practice tithing, although it was later adopted by the Catholic Church in the Sixth Century A.D.

Upon presenting the research paper to my supervisor, I was treated in a manner reminiscent of Galileo's encounter with the Catholic Church. I was warned that I had better keep my findings and views to myself. Naturally, it was assumed that I had done the paper because I had some kind of ax to grind and was merely out to prove a previously held notion. Research at Ambassador so often has meant nothing more than finding "proofs" for the "inspired" concepts and ideas of the Armstrongs.

When I was asked to squelch my ideas, I pointed out that that might be difficult as four people had already seen the paper. I was told that if I would keep it down, a doctrinal committee (sic) would eventually consider my findings. Six months went by and about all that the so-called doctrinal committee accomplished can be seen by reading a booklet entitled MARRIAGE AND DIVORCE published briefly by Ambassador College in the summer of 1973.

When I concluded there was no reason why I should keep my paper from others, I proceeded to show it to anyone who inquired about it. Not believing I was the ultimate authority on the subject, I collaborated with a team of some six other Ambassador College researchers on a more in-depth paper on tithing which was completed in December 1973.

As a result of these papers and the fact that I no Ionger felt a religious compulsion to practice tithing, I was dismissed, without warning, from my job on January 7, 1974. This happened despite the fact that my new supervisor, Dr. Robert Kuhn, acknowledged that I had done outstanding work for him. So much for religious freedom at Ambassador College.

The paper in question was ultimately published with minor modifications by both the Foundation for Biblical Research and the Associated Churches of God. Some open-minded researchers for a newly reconstructed doctrinal committee which was investigating tithing confided to me that any thesis or dissertation from reputable theological institutions that they had the opportunity to examine dealing with the subject in question, tended to agree with my findings.

Finally, in a meeting called to investigate the origin of the papers published by the Foundation and Associated Churches, I was publically slandered by Ambassador President, Garner Ted Armstrong. Armstrong stated, "Now I don't express it as assassination of Harry's character-it is his mind I'm worried about and not his character. I'm not a bit worried about his personal integrity or his personal habits nor his personal sincerity, but I'm not prepared to say he is the most balanced individual mentally, and that I would rely an awful lot on his research."

But he had been relying "an awful lot on his research". Just weeks before, Armstrong had been parroting my findings on his television program seen by millions in the U.S. and Canada. Furthermore, many of these programs were repeated on the air over and over again. On more than one occasion, articles bearing the by-line of Garner Ted Armstrong but researched by me appeared in fire PLAIN TRUTH magazine.

Only when my findings disagreed with Armstrong's private views was my research no longer reliable and the writer fit for ridicule. But such are the risks that anyone takes who might dare disagree with the administration.

-Harry Eisenberg

Editor: Harry's efforts to obtain the truth about tithing represented a special threat to the Ambassador administration. It is the one threat Ambassador fears the most-the threat of individual integrity asserting itself over Ambassador's aristocratic corporate structure.

Consequently, on January 7, 1974, Harry Eisenberg's hopes of a fair hearing for tithing research died by committee. Harry's voice, as well as his research, had to be removed from among the followers.

The Ambassador College Board of Trustees found nothing sinister about Harry's removal. Ministers and students who had liked him apparently found nothing objectionable in his being disfellowshipped. "He was a youth overly exposed to satanic doctrines, demonic thoughts goaded him into an attitude of rebellion. Nothing unusual in that." It ended, however, in his dismissal from an organization to which he had dedicated his life.

The announcement of Harry's termination took less than a few seconds. There was no risk that the doctrinal committee would expose the true reasons for Harry's dismissal, because members of that committee had been a party to it. There was no risk of exposure from members of the Ambassador-controlled media because a few words about the "Ambassador Oasis" from the charismatic Ted Armstrong, and the students would inquire no further. They would not try to digest the indigestible, think the unthinkable, or question Pilate about the removal of a christian.

No, on January 7, 1974, all seemed well. In fact, things seemed better than ever. And, in short time, the people would again be reminded that "God's work is moving ahead stronger than ever."