Ambassador College (AC) has once again failed to receive regional accreditation from the Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC). WASC did extend candidacy for another two years, but, although this was encouraging, this extension should not be regarded as a guarantee of imminent accreditation. When Herbert W. Armstrong (HWA) founded AC, he said he was establishing it for a definite and far-reaching purpose and promised to maintain standards on a high level “to insure full accreditation before the graduation of the first senior class” (Ambassador College Catalog, 1947-48). Twenty years later in 1968 AC was still looking forward to the possibility of becoming accredited. In 1976, Garner Ted Armstrong (GTA), president of the college, declared optimistically, “We’re pursuing accreditation, and we believe we’re going to get it” (Bible Study, Feb. 27, 1976). Later that same year HWA informed his congregation that “the way had been cleared for the accreditation of Ambassador College” (sermon, Mar. 6, 1976). But in June 1977, almost 30 years since HWA had founded AC, WASC again voted to deny accreditation to Ambassador.

To most students, faculty, and administrators this came as a crushing blow. Many were banking on the idea that the college was for all practical purposes accredited. AC had been transformed from a ministerial training school to a real academic community. Many felt that AC’s stature had progressed to the point that WASC should have, at the very least, granted provisional accreditation to the school. For what reasons then was AC denied accreditation? Were the problems that caused the denial academic in nature or blatant continuation of strong-armed administrative practices? It is important that these reasons be discussed so one can understand why AC has consistently missed the goal of accreditation.

It must be noted that AC was not denied accreditation because of one or two picky points. In its letter of denial to the college WASC listed no fewer than 13 recommendations that would have to be implemented before the college could become accredited:

· Plans for alleviating space problems in the library and elsewhere, and provisions for employment of additional fulltime faculty should be given high priority.

· Without abridging the present supportive relationship between Ambassador College and the Worldwide Church of God, a complete separation of church and college must be established and maintained. This would also make possible financial reporting more in line with standard college practices.

· Since several persons hold major roles in both the church and college, unusual care must be taken to avoid the conflict of interest which such dual responsibilities can generate.

· Each department should assess its capabilities and limitations so that plans for the future are in harmony with an institutional commitment to carefully controlled growth.

· The proportion of the budget devoted to physical plant and support services should be reviewed so a more equitable relationship with the academic program can be established.

· A program to help members of the board of trustees understand their duties should begin immediately and should be a continuing and explicit effort.

· The executive committee of the trustees should have its role, including authority and composition, developed and assigned by the full board.

· Faculty involvement in such areas as budget development and handbook revision should be sought out and formalized.

· Administrative relationships and titles need to be stabilized and a comprehensive management study undertaken.

· Procedures for involving students in campus government need to be reviewed, and help for students should be as responsive as possible to actual student needs.

· Course sequence needs to be made more realistic, and facility equipment in the joint sciences should be upgraded substantially.

· A conscious effort needs to be undertaken to insure that able and dedicated women on the faculty are appointed to committees concerned with full college policies.

· Steps should be taken as soon as possible to see that the campus is prepared for an OSHA (occupational safety) inspection.

One should notice that well over half of these points deal with difficulties at the administrative level-most of which WASC had warned the college about time and again. Because the Armstrongs are bent on maintaining the political status quo and have only implemented minimal cosmetic changes, one might seriously ask if Ambassador will ever be recognized as a legitimate four-year college.

WASC did say, however, that AC’s academic posture is moving closer toward “the mainstream of private higher education.” Many administrators, members of the faculty, and students have worked arduously formulating a curriculum, structuring course outlines, and generating reports for the various committees and task forces. But all their efforts will be in vain if they do not confront these administrative problems.

Aerial view of Ambassador College’s opulent Pasadena Campus Aerial view of Ambassador College’s opulent Pasadena Campus |

Six major areas were covered in WASC’s evaluation report of its March 21-24, 1977 visit. For the sake of clarity and continuity these same areas of study will form the basic outline for this article. It must be determined whether Ambassador College is actively and seriously seeking accreditation or merely mounting another monumental snow job with the hope of pawning off more cosmetic changes as genuine compliance to WASC’s recommendations.

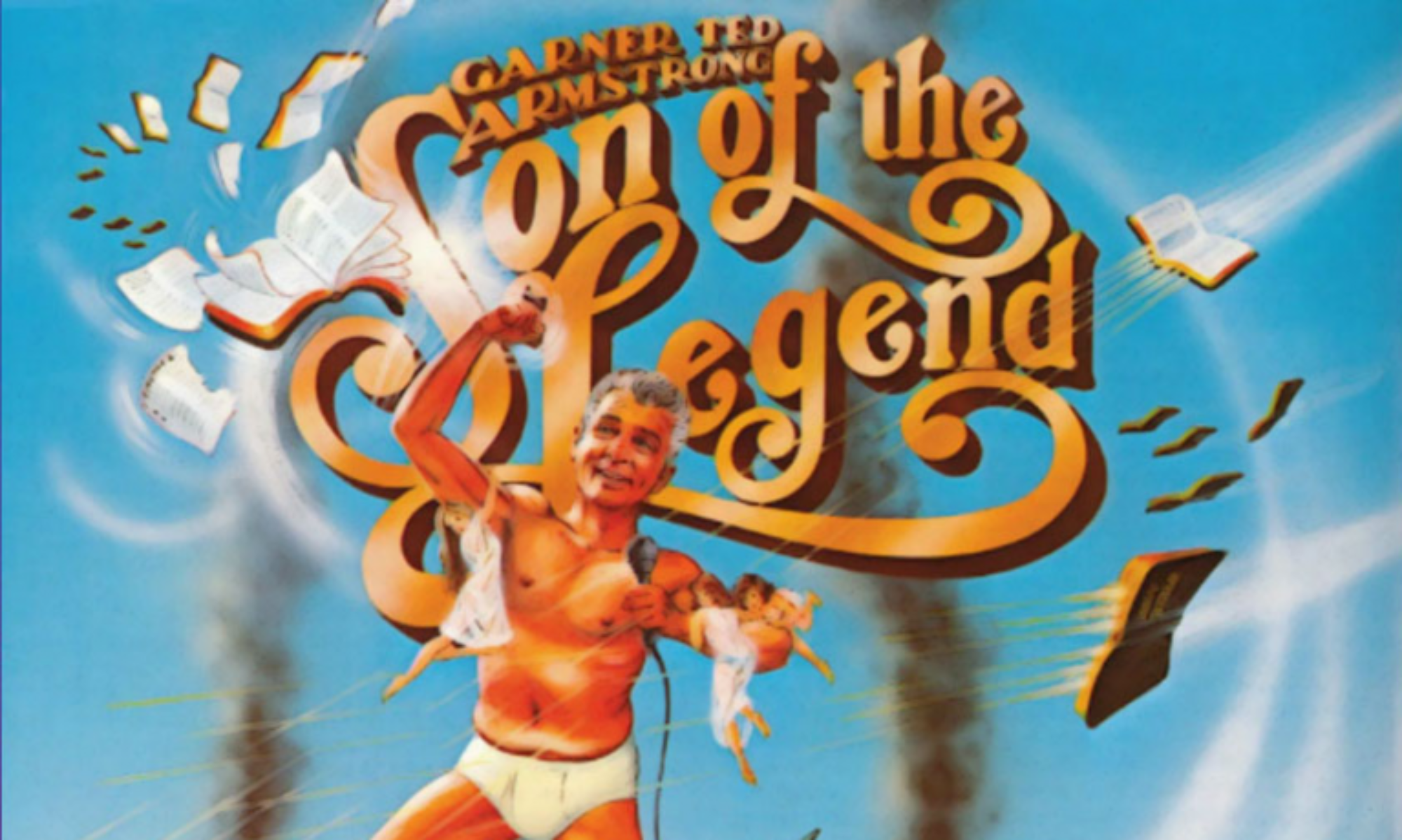

I. Administration. On the surface AC has undergone substantial administrative changes since WASC’s 1974 visit. Foremost of these was the appointment of a new president. (At the time of the 1974 evaluation, Herbert Armstrong held the dual titles of chancellor and president of the college; currently Garner Ted Armstrong is president of the college.) In addition, AC’s Board of Trustees has again been reconstructed by the Armstrongs. (The board has been enlarged from seven to fifteen members.) But important changes were still being made as late as mid-March of 1977, less than two weeks before the site visit. WASC noted this and stated that although the ability to change quickly was impressive, “rapid change can also suggest that administration is not taken very seriously [and]… that precise relationships and clearly defined areas of responsibility simply do not exist” ( WASC Evaluation Report, 1977).

This lack of clearly defined administrative responsibility exists because of the authoritarian governing policies practiced by the Armstrongs and their lackeys in both the Worldwide Church of God and AC. Because of the absence of a working system of checks and balances at AC, changes can be-and often are-made rapidly without evaluation. This authoritarian approach to administration has no place in an academic institution. If Ambassador is truly desirous of accreditation, it must make a sincere effort to separate itself from this heavy-handed practice of “church government.” If the new Board of Trustees will take its rightful position in the area of governance of Ambassador College, it is more than likely that these problems can be solved.

But what about the Board of Trustees? Is it a viable working body or an extension of the Armstrong authority machine?

Since 1974 the physical complexion of the board has changed substantially. When the evaluation committee visited the college in October 1974, there were seven members on the board. Six of them were ministers (HWA, GTA, Ron Dart, Dibar Apartian, Ben Chapman, and Herman Hoeh). The sole nonminister on the board was Shirley (Mrs. Garner Ted) Armstrong. At that time the examiners recommended that the board should be enlarged and that “…there should be more of a ‘mix’ in Board composition, even to the extent of allowing non-Worldwide Church of God representation…” (WASC Evaluation Report, 1974). Subsequent to that suggestion the board was enlarged to fifteen-eight new members were appointed and took their places by the original seven. None of these changes in size or membership substantially altered the political composition of the board, however. This basic structure existed until mid-March of 1977.

Just prior to this year’s evaluation committee visit, AC officials decided to comply more strictly with WASC’s 1974 recommendations. In the interest of disclaiming the practice of nepotism and possible accusations of conflict of interest (especially in the case where a board member was also a college administrator or if a person was a member of both the college and church board) and in order to provide for a greater “mix,” the composition of the membership was changed. AC’s 1976 Institutional Self-Study Report (p. 98) boasted that “the Board has been expanded to fifteen members from varying backgrounds.”

It is interesting to note that the majority of these “members from varying backgrounds” are or have been high-ranking church officials who receive some kind of monetary remuneration (either salary or retirement) from the college or the WCG. Current members of the board are Herbert W. Armstrong (chancellor of the college, pastor general, and self-proclaimed apostle of the church), Stanley R. Rader (vice-president for financial affairs; his firm audits the books for the college and church), Frank Brown (minister), Jack Elliott (retired), David Jon Hill (semiretired evangelist), Brian Knowles (minister and managing editor of The Plain Truth), Jack Martin (employee), Raymond McNair (evangelist), Richard Rice (minister), Harold Treybig (minister), Dibar Apartian (evangelist), C. Wayne Cole (evangelist and head of the Canadian ministry), Harold Jackson (minister and head of the black African “Work”), Elbert Atlas (minister), and Van Lisman (optometrist and laymember of the WCG). All are members of the Worldwide Church of God. (WASC’s recommendation of allowing non-Worldwide Church representation was evidently ignored.) Although these men (there are no women on the board) may in fact come from varying backgrounds, it is hard to see how one could consider that this change has altered the situation significantly. Because of their close relationship with the WCG, their ability to operate independently from the church must be questioned.

On March 15, 1977, several days prior to the WASC visit, a board meeting was called. This meeting was designed to belatedly instruct the board members about their responsibilities and functions. Ralph Helge (attorney for AC and the man instrumental in drawing up the most recent Ambassador College Handbook, as well as much of the “new” board’s policy and procedure) lectured to the new and continuing members about the parameters of their authority. In summary the material outlined by Helge stated that board members must be members of the WCG in good standing; the board is empowered to nominate and elect its own members; its primary responsibility is the setting of general policies; and it has delegated authority to the president to implement them. All administrative officers are answerable to the board, including the president. If these indications are accepted on face value, one would assume the Board of Trustees is finally in a position of authority and capable of instituting changes that will assure the accreditation of the college. Unfortunately, this is not the case.

Just before the adjournment of the March 15 board meeting, President Armstrong interjected the following disclaimer.

“In case anyone has the slightest little idea, ‘Well my, doesn’t this look like we’re putting in a totally different system of government?’ let me assure you, let me assure you that the… government of God, from the top down-meaning my father in his position and me in mine-will be secure, and there is no diminution or dissolution of church government” (Board of Trustees meeting, Mar. 15, 1977).

President Armstrong made it perfectly clear that he expected no power struggle or exercise of power on their part. In essence the Armstrongs have established another “rubber stamp” Board of Trustees.

More evidence that shows President Armstrong feels he is above the board’s authority rather than under it is found in a statement he made in his “Personal” in the July 18, 1977, issue of the Worldwide News:

“…A search for qualified lay-membership representation on the board is under way, and I am evaluating a number of dossiers submitted for presentation to the board at an early time….”

According to the official organizational report submitted by AC to WASC just previous to the evaluation committee’s visit, the president is appointed by and is subject to the board. Since this is the case, what authority does GTA have in reviewing these dossiers in preparation for presentation to the board? Rather, this should be the function of the board itself. Either this is a classic example of the tail wagging the dog (in which case the board should remind the president with regard to the proper chain of authority), or it is a blatant confirmation that the Board of Trustees is the sham it always has been.

In essence, what is being exhibited here is nothing more than unabashed double-talk. It is no wonder, then, that WASC noted some confusion among faculty members as to “what is expected or allowed them in matters of college governance generally, or even in academic planning” (WASC Evaluation Report, 1977). Although AC does have a statement (of sorts) on academic freedom and responsibility (which was drawn up by the college’s legal department without faculty consultation or input), it is ambiguous and confusing, to say the least, and must be categorized as more of the same-unadulterated doubletalk. The statement that was printed in the Ambassador College Handbook in section 4.2 follows:

“Academic freedom shall be understood to mean that the faculty member is encouraged in the pursuit of knowledge and truth within the area of his instruction and is expected to teach different viewpoints about secular knowledge.”

Without an exact definition of what is meant by “secular” knowledge this statement is meaningless. On the surface “secular” knowledge could be interpreted as meaning anything not religious. This would be the most likely interpretation for a person to chose if uninitiated to the WCG’s special approach to education. The WCG does not accept “secular” knowledge of and by itself because it claims all knowledge has its spiritual dimension. All knowledge must be evaluated from a particular spiritual perspective. Unless one views all knowledge in line with the established view of those in charge (i.e., HWA and GTA), then he is accused of being out of line with the teachings of the church and dealt with accordingly.

Under no circumstances could AC’s statement on academic freedom be defined as strong and definitive. In fact, because of the limitations within the statement, it does not even conform to the current interpretation of academic freedom by the American Association of University Professors who stated:

“If a limitations clause at a church-related institution leads to elimination of the basic expressions of academic freedom, the institution has lost its credibility as a member of the academic community” (AAUP Bulletin, Vol. 61 [Spring 1975], p. 57).

Ambassador College must clear up the confusion regarding the policy or rather the lack of a policy on academic freedom. A refusal to do so may result in a loss of key faculty members as well as continued denial of accreditation.

In a recent move to comply with WASC’s suggestion that AC should become separate from the WCG in financial affairs, President Armstrong appointed Dr. James Stark (who was chairman of AC’s Business and Economics Departments) to replace Ray Wright (who held the position of business manager for Ambassador College, the church, and AICF) in the position of business manager for Ambassador College. But this is just a small step. WASC emphasized that much remained to be done before the college could present a “truly convincing” picture of financial accountability. Foremost among their criticisms was the intertwining of assets between church and college. They also stated that AC “would benefit substantially from a very comprehensive management study, including a thorough audit, by a nationally recognized firm” (WASC Evaluation Report, 1977). The institution’s financial records are currently audited by the accounting firm of Rader, Cornwall, and Kessler (a clear example of conflict of interest, since Rader is a member of the college Board of Trustees and holds other major positions within the institution). If Ambassador desires to become and remain accredited, it really has no choice “but to demonstrate that the college is a distinct entity from the Church.”

The overlapping of church governance with the administration of the college has no place in Ambassador-especially if AC truly expects to become accredited. The Board of Trustees should exercise the power that is rightfully theirs and institute the changes needed to clear the way for full regional accreditation. (It is highly unlikely that this will ever take place, however, because 13 of the 15 board members are payed by either the church or the college-Garner Ted signs the checks.) If the Armstrongs continue to thwart the decentralization of administrative power, WASC will be forced to again deny AC accreditation.

II. Physical Facilities and Equipment. Only brief comment is necessary for this category. It goes without saying that the campus grounds are beautiful and create an environment of serenity. A major drawback confronting the college, however, is the severe shortage of space and in many instances equipment. The evaluation committee summed up its feelings in this area by stating:

“The cost of maintaining such a magnificent campus needs to be scrutinized carefully, however, so that the College cannot be justly accused of being more interested in how a program is accommodated than in the program itself. A lovely facade is no substitute for a solid, if plain, academic effort” (WASC Evaluation Report, 1977).

III. Library and Other Learning Resources. Since WASC’s 1974 visit, AC’s Library and Learning Resources Department has grown and developed into a more important and viable resource in the academic community.

Currently this department is housed within five buildings. WASC considered the scattered physical locations and inadequate storage facilities a major liability in this area and suggested that housing this department under one roof would alleviate these problems plus speed up the process of converting to a single classification system. (The library is in the process of changing from the Dewey Decimal System to the Library of Congress System.) Also, foremost among WASC’s suggestions was that AC should increase the library’s budget to enable it to hire three or four full-time staff members and that the current budget for library material be continued with annual increments for inflation.

For the most part these suggestions seem straight forward and will not cause undue hardship on AC to implement-that is, if AC is granted ownership of the Vista del Arroyo Hotel property and there is no shortage of funds.

It must be pointed out, however, that AC’s library is another example of administrative lethargy. Although in many ways the library has made tremendous strides in overcoming blatant inadequacies, overall the facilities are still inadequate to meet the needs of the students and faculty of AC.

These points were glossed over and in some cases completely deleted from AC’s official 1976 Institutional Self-Study Report, which was prepared specifically for WASC. In fact, the administration will again have to stand accused of trying to snow the evaluation committee. The original report submitted by the special student-faculty task force that studied the library and the other learning resources was deceptively altered by upline administrative officials. What AC published in the self-study report and what the student-faculty task force actually wrote were two different things.

For example, under the heading “Student Questionnaire Results,” the library task force reported:

“Students strongly indicated that the study facilities of the A.C. Library are inadequate. Two hundred ninety-three (63 percent) responded that they spend less than 10 percent of their study time in the Library. One hundred thirty-five responded that the Library is too congested, and 59 reported that too much noise is a problem. Fifty-eight stated that better study areas are needed” (p. 8).

When the report of the library task force was published by AC’s administrators in the self-study, all that they allowed to be retained from the original report was the following:

“Students indicated that there were not enough study stations” (p. 76).

Another case in point was the section on the appraisal of facilities. Notice what the original student-faculty committee reported in their task force report:

“Results of the March 1976 surveys conducted by the Library and Learning Resources Task Force indicate that students and faculty of Ambassador College find library facilities inadequate for their present needs” (Library Task Force Report, pp. 10-11).

Now notice how the text of the task-force report was radically altered by the administration. The self-study reported just the opposite:

“Results of surveys indicate that students and faculty of Ambassador College find library facilities adequate for their present needs” (1976 Institutional Self-Study Report, p. 78).

In this same appraisal section under the category of “Funding” a similar altering is found. First, notice the original evaluation of the task force:

“Collection deficiencies have arisen because funds for library development have not been commensurate with the rapid growth of the curriculum. Since the 1973-74 academic year, 264 new courses have been introduced into the curriculum. While there have been modest increases for current journal subscriptions and reference materials, course-related book expenditures have remained essentially at the 1972 level…. Because 264 new courses have been introduced since 1973-74, appropriation of between $198,000 and $211,000 beyond the normal operating budget should have been made. Unfortunately, these funds have not been made available; therefore, library development has not kept pace with the rapid growth of the curriculum” (Task Force Library Report, pp. 14-15).

Now read how AC’s leaders tried to cover up the library’s real problems by publishing statements diametrically opposite to what the task force found and reported:

“Certain collection deficiencies resulted because funds for library development have been limited. However, a special $25,000 appropriation for library development was included in the 1976-77 budget. The proportion of institutional expenditures for library operations is in line with the 1975 Standards for College Libraries. Special funding such as the $25,000 appropriation should help to overcome any long-term collection deficiencies” (1976 Institutional Self-Study Report, p. 80).

These changes did not constitute a minor rewording here and there, but were underhanded attempts by those at high administrative levels to create a better picture than actually existed by (1) distorting the facts and (2) withholding negative information found in AC task-forces reports. One wonders how AC can claim to be a character-building institution if its leaders are guilty of such deception. Obviously those in control at AC are more interested in the cosmetic appearance of AC than in its inner strength or weakness. Rather than appropriate enough money for the library, they chose instead to build four tennis courts, to contribute $250,000 to build a playground in Jerusalem, and to pour six million dollars into Quest/77.

IV. Educational Programs. Ambassador College offers a broad range of majors for such a small college. On the surface it appears to be a well-rounded program. In terms of facilities and the logistics of implementing these programs in certain areas, there needs to be a greater coordination. While solving these difficulties is of major importance and will take some time, they are for the most part growing pains which will disappear with the development of the faculty and a careful analysis of each program.

V. Instructional Staff. Since the fall of 1974, the faculty of Ambassador College has increased in size from 72 to 132 (1976 Institutional Self-Study Report, Table 11, p. 52). Academically the faculty composition has provided the strength that has allowed the college to reach its current level of academic professionalism. A major weakness that must be confronted, however, is that many are only part-time personnel and cannot devote full attention to the needs of a growing institution.

A problem that the college may be facing in the future, however, is the loss of key personnel-especially those who are not members of WCG. In light of the problems concerning academic freedom and tenure, plus the question of whether or not AC is making strides to solve its administrative problems, some instructors are reevaluating their professional careers and are wondering if they are not just wasting their efforts because of the lack of commitment on the part of the Armstrong administration to allow the necessary changes. Unless AC administrators quit their foot-dragging, Ambassador may stand to lose more than a few instructors. Without a strong faculty AC cannot expect to be accredited.

VI. Student Activities. The college offers a wide range of student support services that are, for the most part, controlled by the administration. Student body officers are handpicked and appointed by the administration rather than elected in a general student body election. WASC even suggested that the college should “study the feasibility of selecting student body officers through elections rather than appointment by the administration” (WASC Evaluation Report, 1977). President Armstrong has made it perfectly clear, however, on several occasions that “democracy will not flourish at Ambassador College.”

Since such doctrinal teachings of the church pervade even the area of student government, it isn’t surprising to find that freedom of speech is also in short supply. Censorship of the Portfolio, AC’s student newspaper, is an example of this. Any subject which is considered too controversial will be summarily axed from an issue. If an article or editorial disagrees with some administrative policy, the same thing happens. This past spring one of the Portfolio staff reporters wrote an article criticizing the extravagance of a particular party and dance that happened to be President Armstrong’s brainchild. Needless to say, his article was never printed. But to top that off, President Armstrong called the student into his office for a conference. The student was threatened with dismissal and loss of a scholarship. This kind of action can only be detrimental to the college as a whole.

If students subject themselves to this kind of action, they are only kidding themselves. With the obvious lack of practice of academic freedom for the students, it seems unlikely that the institution will be accredited in the near future.

Conclusion. In the past four years Ambassador College has experienced tremendous academic growth-which can be attributed to the maturity and dedication of the faculty and some members of the administrative staff. Ambassador has been transformed from a vocational training center for the Worldwide Church of God into an institution of higher learning. It has come of age and must separate itself from the Worldwide Church of God and its government.

So far, the Armstrongs’ selfish desire to maintain their rigid control over the institution-even to its detriment-has prevented it from becoming accredited. But while the Armstrongs must bear the main responsibility for AC’s inability to achieve accreditation, the other administrators, faculty, and especially board members who claim their hands are tied in the matter will also be held accountable because of their silence. For by their silence they in essence condone the chicanery.

Students who have been lured to AC by the siren song of the finest this and the finest that, who have listened to the hollow promises of imminent accreditation, and who have wasted their money and time on a practically invalid degree are the real victims. Many who have gone back to pursue higher degrees at other colleges found that they were forced to backtrack-sometimes for four years before they could continue into a Master’s or Ph.D. program. A few have been more fortunate and have only had to pick up a few credits in core courses to pursue their desired degree. But no one needs the problems associated with an unaccredited degree.

In the final analysis it boils down to this: Unless AC’s Board of Trustees makes a definite decision in the next few months to honestly alleviate the Armstrong authoritarian stranglehold on them, it is more than likely that accreditation will continue to be Ambassador’s missing dimension in education.

-Margaret D. Zola